Part Four: Congregation/Congress v. “Church”

From SaveTheWorld - a project of The Partnership Machine, Inc. (Sponsor: Family Music Center)

| Forum (Articles) | Offer | Partners | Rules | Tips | FAQ | Begin! | Donate |

So what is Jesus building, that the Politics of Hell has tried with all its might to snuff out but has utterly failed?

King James’ “Church”

When King James organized the translation which bears his name, he had 15 rules for his team of translators. Some were common sense rules about how to divide tasks and double check each other. But a couple of rules were James’ grab for ecclesiastical power.

One rule prohibited margin notes, which had made the Geneva Bible so helpful, but whose observations about tyranny had infuriated James.

Another rule required copying as much of the Bishop’s Bible (the official Anglican Church Bible translated under Queen Elizabeth’s direction in 1568) “as the truth of the original will permit.”

Only one rule dictated how a certain Greek word had to be translated. Only one word mattered that much to the king, to force England’s top Greek scholars to translate one particular Greek word not according to its meaning but as the King demanded.

That English word was “church”. That was the royal translation of the Greek word “ekklesia” (εκκλεσιαν).

Here is the text of the royal decree: “3. The old ecclesiastical words to be kept; as the word church, not to be translated congregation, &c.”

Who had translated it “congregation”? What happened to the guy who translated it “congregation”? What is the big difference between “church” and “congregation” that the king made such a big deal out of it?

Thank you for asking. William Tyndale translated the word εκκλεσιαν as “congregation”. For translating the New Testament into English, he was strangled and then burned at the stake. Although he was murdered for translating more than one word, King James’ focus on that one word suggests that one word very likely rankled his predecessor, King James’ great grand-uncle, King Henry VIII, similarly.

The big difference? James called “church” an “ecclesiastical word”. “Ecclesiastical” refers to a very regimented church structure, with rich uniforms and elaborate rituals. King James wanted his Bible to support that. Why?

Both the Catholics and the Anglicans preferred dogma, richly endowed churches and brilliant ceremonial as an integral part of the worship of God, and both claimed for themselves absolute authority over their clerics and their congregations – and the unassailable right to order their services in the manner established by their “princes”.

The Puritan concept of worship, however, included no dogma, no ceremonial, no statuary [statues] and no formal Book of Prayer. It despised the panoply [ceremonial robes], the preferments [titles and powers], the dignities and the rich emoluments [salaries] of the self-appointed bishops and archbishops and resented fiercely their claim to infallibility and their rejection of the right of any man to worship in accordance with the dictates of his own conscience.

It disdained the vestments of the clergy and their ritualistic services, and utterly rejected the use of symbolism in the form of Holy Mass, Communion, Baptism, the Enthronement of Bishops and the Solemnization of Marriages. They claimed the right to elect their own teachers and objected strongly to being compelled to support the magnificent edifices of church and cathedral through tithes, levies and taxes – preferring to worship solemnly in humble surroundings and in direct communication with God.

But the state religion of England had the advantage, as far as King and government were concerned, of forming a vast network of communication that reached into every corner – and every home – of the realm. Through it ran the authority of the law, the injected fear of the hereafter and the certainty that the vast army of priests employed by it must, inevitably, note the slightest reluctance on the part of anyone to comply with its ordinances. Compulsory attendances at church services ensured that the “Big Brother” technique of surveillance was total; mysticism at those services created fear, the brilliant ceremonial awe – and the parish rolls prevented the citizens from dispersing and so evading taxes, military service and their “duty” to their masters. For those who failed to conform, the penalties were severe and summary. (The Mayflower, by Vernon Heaton, pub. Mayflower Books, New York NY, p. 9)

That helps explain why King James wanted “ecclesiastical words” in his Bible. They made possible his rule as absolute dictator. Similarly today, though to no such lethal extent, the Noninvolvement Theologies permeating most churches fairly insulate government from organized Christian influence. They keep the Salt mostly in the Saltshaker. They keep the Light mostly out of the Darkness.

“Congregation”, the translation that enraged kings

But doesn’t “congregation”, Tyndale’s translation, simply mean “the members of the church who listen to a sermon every Sunday”? Don’t “congregation” and “church”, therefore, mean practically the same thing? So why the royal fuss?

The words didn’t mean the same thing then. But the fact that the words are equivalent today makes it an insufficient correction to merely replace the word “church” with the word “congregation”.

A clue to the difference is in the definition order of the word “congregation” in a modern dictionary, compared with the definition order in an 1826, 1755, and 1604 dictionary.

Contents

1604

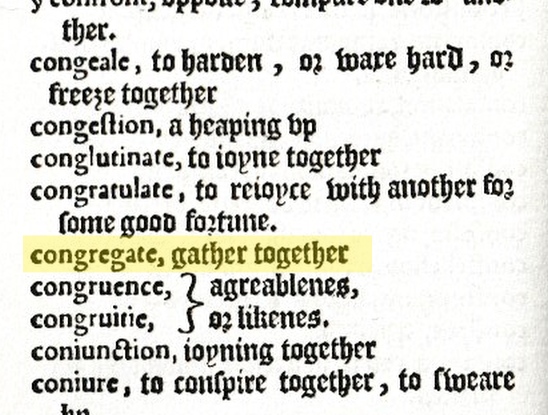

In the 1604 dictionary, “congregation” wasn’t even listed; the closest word was “congregate”, which meant “gather together”. No religious association is recorded.

A 1526 dictionary would be a more accurate indication of what the word meant when Tyndale wrote it, but the first English dictionary was in 1604 and it was abbreviated.

There was not another English dictionary until 1755, and then not another until Noah Webster’s 1828 dictionary, the first American dictionary.

“Church” did not have its own separate listing either in 1604, but it is given as a synonym of “cathedral” which is “chief in the diocese”. In order to teach his readers how to find words, readers had to be taught the new concept of alphebetizing words.

This is the title page of Robert Cawdrey’s 1604 dictionary. The most noticeable difference in appearance between spelling then and now is that “s” was often written like an “f” without the cross bar. “U’s” were sometimes written as “v’s”.

Cawdrey’s stated motivation for creating his dictionary was to help people read “Scriptures, Sermons...” Cawdrey was a Christian who taught in school beginning in 1563. By 1570 he was a priest, but by 1588 he had violated enough Church of England restrictions, such as reading from unapproved texts and sympathizing with Puritans, that he lost his rectory and had to return to teaching. By “hard” words, Cawdrey meant unfamiliar foreign words flooding into the English language. He was concerned that parents were losing their ability to understand the vocabulary of their children.

King James’ orders had given “church” as the example of “ecclesiastical” words which his translators were required to use. Cawdrey’s dictionary, published the same year King James issued that order, defines “ecclesiastical” as “belonging to the Church”.

It was natural for the word “congregation” to acquire an association with the Church of England over the generations just from being Tyndale’s translation of assemblies in the Bible which most people assumed were exactly like the “church” down the street.

1755

Yet even as late as 1755, when Samuel Johnson published the first dictionary of the English language featuring more than 3,000 words and more than one definition per word, (Noah Webster published the first American English dictionary in 1828) “Congregation” (from “congregate”) still had a religious meaning in last place.

1. The act of collecting. “The means of reduction by the fire, is but by congregation of homogeneal parts.” - Bacon (Francis Bacon, 1561-1626)

2. A collection; a mass of various parts brought together. “This brave overhanging firmament appears no other thing to me, than a foul and pestilent congregation of vapors.” - Shakespeare (William Shakespeare, 1564-1616)

3. An assembly met to worship God in publick, and hear doctrine. “The words which the minister first pronounceth, the whole congregation shall repeat after him.” - Hocker (Richard Hooker, theologian, 1554-1600) [Johnson’s Dictionary]

Notice the dates of the authors quoted by Johnson to show what words mean by their contexts. they are all after Tyndale’s translation. Yet they still do not associate these words with “church”.

The verb form of “congregation”, “congregate”, had zero religious association in the 1755 definition. In fact in the only context offered to show how the word is used, “church” is understood to mean “any multitude of Christian men congegated”, which rejects today’s understanding of “church” as limited to an assortment of rituals from sermons to pastoral prayers to pulpits.

Congregate: To collect together; to assemble; to bring into one place. “Any multitude of Christian men congregated, may be termed by the name of a church.” - Hooker “These waters were afterwards congregated, and called the sea.” - Raleigh’s History of the World “Tempests themselves, high seas, and howling winds, the guttered rocks and congregated sands, as having sense of beauty, to omit their mortal natures.” Shakespeare’s Othello “The dry land, earth; and the great receptacle of congregated waters, he called seas; and saw that it was good.” - Milton’s Paradise Lost “Heat congregates homogeneal bodies, and separates heterogeneal ones.” - Newton’s Opticks. “Light, congregated by a burning glass, acts most upon sulphurous bodies, to turn them into fire.” - Newton’s Opticks.

To Congregate To assemble; to meet; to gather together. “He rails, even there where merchants most do congregate, on me, my bargains.” - Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice “Tis true (as the old proverb doth relate) equals with equals often congregate.” - Denkam [Johnson’s Dictionary]

However, the adjective form, “Congregational”, was associated by 1755 with the particular assemblies of believers who rejected the king’s Big Brother church in favor of the individual freedom and equal voices indicated by Tyndale’s word “congregation” as the institution Jesus would build.

Congregational: from Congregation. Public: pertaining to a congregation or assembly. It is a word used of such Christians as hold every congregation to be a separate and independent church. [Johnson’s Dictionary]

Before the word “congregation” evolved into today’s “the people who go to Church every Sunday to listen to a sermon”, it had blossomed from Tyndale’s word for what Jesus would build into the definition of a kind of church government not seen for centuries: in which congregations elected their own leaders. Today,

Congregationalism speaks of a form of church government. “Episcopal” church government is rule by bishops, “presbyterian” church government is rule by [local] elders, and “congregational” church government is rule by the congregation. Episcopal government usually includes a hierarchy over the local church, and presbyterian government sometimes does as well. Congregational government nearly always avoids such hierarchy, maintaining that the local church is answerable directly to God, not some man or organization. Congregational government is found in many Baptist and non-denominational churches. In addition to those churches which practice a congregational form of government, there are also those which call themselves Congregational Churches. - gotquestions.org.

By 1755, the community established by the Pilgrims (who called themselves “Separatists”) in Plimoth, Massachussetts, had been a successful community for over a century. The Congregational Church in Plymouth (updated spelling) has recently been taken over by the General Society of Mayflower Descendants, and will be fully reopened as a museum in time for the 400th Anniversary of the landing of the Mayflower.

1828

A religious meaning of “congregation” was still down in 3-1/2 place in 1828, when Daniel Webster published the first American English dictionary. Notice that #4 quotes a Bible verse, in which “congregation” refers to a gathering of jurors – a jury in criminal cases:

1. The act of bringing together, or assembling.

2. A collection or assemblage of separate things; as a congregation of vapors.

3. More generally, an assembly or persons; and appropriately, an assembly of persons met for the worship of God, and for religious instruction.

4. An assembly of rulers. Numbers 35:12. [The verse describes people who functioned as jurors do today.]

5. An assembly of ecclesiastics or cardinals appointed by the pope; as the congregation of the holy office, etc. Also, a company or society of religious cantoned out of an order.

6. An academical assembly for transacting business of the university. [Webster’s 1828 Dictionary]

The Word “Church”

The word “church”, by contrast, in Johnson’s 1755 dictionary, had no secular connotation at all, and its association with religion was of the most regimented kind: